In November 2008, with the financial crisis in full swing, Queen Elizabeth attended a ceremony at the London School of Economics. Facing an audience of high ranked academics, she posed a simple question: “Why did nobody notice it?”

How could it be that no one among the smartest economists, commentators, and policymakers in all her kingdom – and beyond – had been able to see the formation of a bubble of such dimensions?

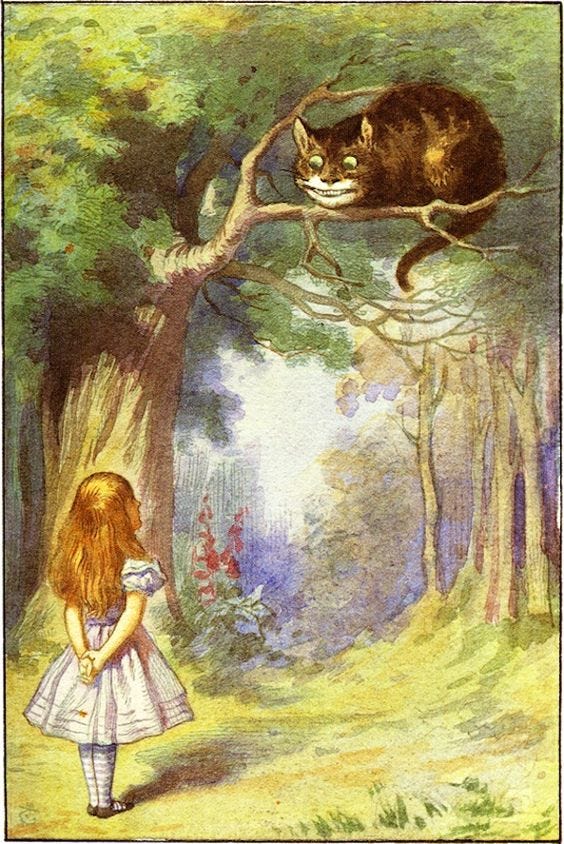

Illustration of The Emperor’s New Clothes by Vilhelm Pedersen, Andersen’s first illustrator

And yet critical facts were readily available – facts that could have warned about the craziness of the housing market, on which an even bigger financial house of cards had been erected. A short trip to a “regular” American neighbourhood – like the one undertaken by Mark Baum in The Big Short – would have presented an endless list of properties under foreclosure, real estate agents openly bragging about the laxity of credit requirements, and exotic dancers with multiple mortgage-financed properties.1

Such evidence would have been sufficient to convince most people of the existence of a bubble. However, in London, New York and the other financial centres of the world, an entire class of experts kept blatantly ignoring the facts, anecdotal evidence, and common sense that could have anticipated what was about to happen.

This is a high profile example of a more general situation in which a narrative establishes itself and resists being disproven, even when it is clearly contradicted by information right under our noses. Like the crowd in Hans Christian Andersen’s famous parable, we watch our sovereign parading naked in the street, but are unable to see through his invisible clothes. Until a young boy steps forward and with a little common sense lifts the veil on our “common talk”.